Studies, theories, ideas, notes from the workface and occasional bits of stupidity.

Saturday, 15 December 2012

Good News?

However, it is, unfortunately, still only a politico talking, and I've become quite used to the sight of people who have been elected to lead waffle on about subjects on which they do not have a clue. Ed's well-intentioned speech is an example of this - he may want people to speak good English, but which variety of English is he talking about?

An interesting (but somewhat frustratingly generic) article on the BBC yesterday points out that not only has English already started to branch off into new varieties (Hinglish, Singlish etc), but that the rise of the Internet appears to be leading to the development of, at present, different ways in which English is used as one of the primary communication tools, and that within twenty years it is likely that a new 'international' variety of English may well evolve.

This is important for us teachers, as users of different forms of the language (rather than learners of English) offer significantly different challenges. My Nepalese learners, for example, have perfectly adequate English, it's just that theirs is a) highly repetitive b) delivered in relatively simple sentence structures and c) about 60 years out of date. Combined with a pronunciation that can be difficult to unpick, it means that while they speak and use English to near-native standard, they cannot function in the L1 environment particularly effectively.

Now, obviously, there's little point in teaching them English per se - instead, I have to teach them a different variety, and that requires not only things such as pronunciation and vocabulary, but also an understanding of cultural differences between the two varieties and different standards in things such as written style. In fact, what this amounts to is a very different beast from the standard 'start from beginner's English and work your way up'-type lesson.

But back to Ed - what does he then mean, 'they must speak English to be integrated?' I don't think he actually understands that it is not, as it were, just about being able to say 'hello', 'goodbye' and 'awful weather, isn't it?' in a somewhat strangulated voice - in this way, he resembles pretty much every politico for the last twenty years who has pronounced grandly on the subject of Foreigners In The UK. By and large, as a nation, we are fantastically good at integrating waves of immigrants - the recent headlines about London now having a minority population of White British native born citizens is actually nothing new - the capital has always been a melting pot For example, during the 18th century, it is estimated that there was a population of some 20 - 30,000 people of African origin living and working there, and they certainly didn't just die off or disappear - they became integrated into the general populace.

What I think Ed wants is people who use language with clarity, and that's a very different proposition from speaking and using English in a particular way. After all, you'll find that significant amounts of business, worth billions upon billions of pounds, is conducted in what is ostensibly English, but not of a variety that would necessarily pass a Skills for Life Exam. As well as ensuring that people can communicate effectively, what also needs to be considered are things like cultural nuances and refernces, and the infuriating habit English has of constantly evolving, with words and meanings popping into and out of existence at the drop of a hat.

Unfortunately, the well-intentioned and ever so goody-two-shoed ESOL Skills for Life Syllabus isn't really fit for purpose on this count - it is, to put it bluntly, a Plodder's Course, designed to ensure that the majority can scrape by and get a qualification. While it addresses fundamental needs - for example, talking to a GP, or understanding a letter from the council -it does not seek to provide challenge, and it certainly is not going to produce the kind of results that Ed thinks we need to staff his 'front-line' services with smiling, fluent users of English Like What It Is Spoken Dahn In Laaaanndahn, Innit?

In fact, the very people he is talking about are ALREADY delivering 'front-line' work - they are carers, teaching assistants, cleaners, nurses, cooks, refuse collectors, working in call centres and shops, doing anything to get by and get on and get up in life. They don't all necessarily need to speak in one variety of English - if that were the case, should we then prevent Aberdonians or Geordies from working in hospitals in the South of England? I agree that some professions need specialised work - Nurses, for example, could benefit from pronunciation and intonation courses, especially when their work is with older patients - but the problem is that, in politicians eyes at least, this would be a highly expensive thing to do with little return, seeing as nurses are poorly-paid and have little influence in Westminster. I might also point out that some Native Speaker Doctors could also benefit from elocution lessons.

And what about IT technicians? Some of the best IT workers are non-native speakers of English, or speak a different variety, and it has to be argued that IT is a 'front-line' service - should they all speak a particular government-approved brand of the language?

What Ed, ultimately seems to be saying is that anyone who spends time speaking to English Speakers should be able to speak clear English.

That's right. He's thinking of Call Centre Workers. That's the modern front line for you.

Monday, 26 November 2012

Bullying

Lesson*

A quick entry today about a lesson I delivered on Thursday with an ESOL Level One (CEFR B1-B2; approximately Upper Intermediate) class.This group consists of 19 students of a variety of backgrounds, with a significant group of older Sudanese learners. This class is unusual in that they almost all come from a very well- to highly-educated background, although there are several in the group with less school experience, including one with a highly-disrupted education in Afghanistan, although this particular student is highly intelligent and has successfully adapted to life in the UK.

The college is running cross-college themes: last week was anti-bullying week, and I felt it would be a useful class to do with this class, as I feel that ESOL students who are here long-term in the UK are significantly more likely to be bullied or discriminated against in a variety of contexts, all of which cause further problems for how they live, work, and study. Here's how the procedure went:

I introduced the issue of bullying through an anecdote of mine (in fact, an incident involving a pedestrian who attempted to assault me the previous day!) and checked what the learners though bullying was. I then put them into groups, and, using the whiteboards in the Rubber Room, wrote down the different kinds of bullying people might face, and where. The learners were highly engaged, actively discussing the subject and using their mobile phones to check for vocabulary and sources. They wrote up their ideas in thought clouds, then after that the groups moved around the room, looking at the other groups' ideas. We sat down together and had a brief discussion about the different types of bullying, and concept-checked any new vocabulary or ideas, asking the learners who had written the new vocab to explain it.

I then gave each group a short dialogue each, all based on different scenarios where bullying can take place. These included bullying someone because of their accent, and a racist scenario. I gave the groups enough time to memorise and practise their dialogues, then they performed them to the other class members. The rest of the group had to say what type of bullying was being demonstrated.

Following this, we had a whole class discussion about the kinds of bullying they had experienced while in the UK, and what could be done about it, and who in the college could help the learners if they experienced it.

Finally, during an IT session, the learners read about the college policy regarding bullying and commented about their experiences in an online forum.

Overall, a very satisfying lesson.

*I've decided to add a theme title at the beginning of entries to make it easier to decide if you feel it's worth reading or not. :)

Monday, 19 November 2012

Doing it Methodically.

But here's an issue - I will incorporate it into my teaching practices, not run wildly into its outstretched arms, joyously weeping at what could be a Universal Panacea for language learning. In other words, I'm not totally convinced of it as a methodology. I have been teaching now since October 1993, and

I did some further digging during my research, and do you know that there is not a SINGLE piece of empirical research I can find that suggests that one method or approach in language teaching is actually more efficient or effective than another? There is nothing that says CLT is any better or faster at getting students to learn language than, say, Audiolingualism. There are lots of claims, yes; There is lots of anecdotal evidence, yes; But there is absolutely nothing that proves that one method or approach is any better than any other. You will find all sorts of studies that look at motivation, or teacher talk time, or ideas about language learning or acquisition, or how literacy is the key to learning, but you will not find a single thing that says, for example, 'Grammar Translation works better than Dogme. F.A.C.T'.

Why is this? Well, the obvious answer is that it would be incredibly difficult to run an experiment that directly compares different ELT methodologies. I mean, it's possible - I've calculated that it could be done by kidnapping sets of twins at birth, raising them in their birth languages under strictly controlled conditions with other sets of identical twins, then separate them at a certain age and teach them using two different methodologies, ensuring, of course, that they are regularly subjected to MRI scanning and Tomography to measure changes in their brains. Once they have reached a pre-determined level of proficiency, we should then be able to determine which method is more efficacious. Unfortunately, we would then also have to put down our subjects and dissect their brains, in order to ascertain whether there have been any true physical changes to the lobes that deal with language and vocabulary. And that wouldn't be the end of the matter: we'd also need to do tests on twins at different age profiles to see whether different methodologies are more effective in children or adults, plus double-blind trials in order to avoid the risk of statistical bias. Since we would, sadly, have to vivisect many of our test subjects, I suspect that we may run into one or two ethical and legal issues. We may also run out of money to conduct the experiment to its natural conclusion

Putting all that to one side, there is little enthusiasm to test a method rigorously - instead, an awful lot of time is spent on observations about how we believe people learn, which then leads to assumptions about how a method should work. There has been work done on ascertaining students' attitudes towards various class techniques, but again, these end up as essentially anecdotal and highly subjective - if the student had been taught the same thing in a different way, would he or she have learnt it to the same degree? Clearly, it's impossible to investigate whether someone who has, say, learned how to talk about daily routines via the wonder of Dogme could have learned it better had I been just shouting randomly at them while beating them with a cattle prod - after all, they've already learned it!

I sometimes wonder whether methodology is really about the student at all - instead, some of the things we do in class appear to be about keeping the teacher happy, simply because Stuff Is Happening. Quite simply, we believe this technique or this method works because we are using it, ergo it is good and effective. Let's face it, we teachers need a lot of audio-visual stimulation, and we get that in spades from watching happy student faces bellowing at each other 'You? What you job? Is good?' while running round with little bits of paper.

Here's a challenge for you: Pick a technique, or even better, make one up, and stick to it religiously for a week, keeping a reflective diary, and see if it has an effect on the learning and teaching in class.

As for me, I'm eyeing up the local Orphanage for Foreign Baby Twins........

Sunday, 18 November 2012

blending the trad and the techy....

Though I'd do a quick entry about one of the ways I combine using the iPad in class with using our VLE, Moodle, plus some online software to produce a rounded lesson.

My class (an ESOL Level One group) have been looking at narrative tenses and storytelling. I started off this particular session using 'The £2000 Jigsaw' a listening and speaking exercise from Headway Upper Intermediate, 3rd ed, Unit 3. The listening is actually a genunine text from BBC R4's Today, featuring John Humphries interviewing a girl who found £2000 in ripped up banknotes. Students begin by trying to reconstruct the story from prompts, then listen to check, followed by some more detailed questions. Following this, students are encouraged to speculate why the money had been ripped up in the first place. For this phase, I split the learners up into groups, and asked them to make a storyboard of three scenes for the situation. Each group had a large whiteboard each, and spent time debating what the back story could be, and using their mobile phone-based dictionaries to check vocabulary ideas.

After a while, each group had come up with something like this:

I swapped groups round and they then had to try and tell the story of the other group's picture. While they did this, I took pictures of each story on the iPad and placed them on Moodle. We then went to one of the IT rooms, where I got the learners to log on, view their pictures and comment on them, and read the task assignment, which was to use Dvolver to make their stories come to life in a simple animation.

By the end of the session, each group had produced a short movie, telling the backstory of the missing £2000, for example:

http://www.dvolver.com/live/movies-792863

Overall, a fun, instructive lesson that everyone enjoyed.

Monday, 12 November 2012

A short techy one.

OK, I don't think that this will be the longest post ever, seeing as I'm writing it on my shiny new Samsung smartphone. However, following in the spirit of my posts on using the iPad, I thought it would be expedient to try doing a post with a mobile phone.

I've spent the last few weeks watching how my students use mobiles in class. I'd say just over half of them have smart phones, and of those only half actually make use of them to help on the classroom. Only a handful have anything more than a dictionary installed, and while they seem to show genuine interest in the apps I suggest, they don't seem to be very forward on using the things.

In fact, the only people who do download the apps, or use Moodle on a regular basis, are the students who work on their English outside the class, who go to the library and take out readers, who keep vocab records - in other words, all the students one would expect to do well anyway. So, what on earth do I need to do to make Mr. Joe Average student into a good learner? Because it seems to me that shiny new tech may be helpful, but it doesn't turn anyone into a language learning genius by itself.

And this has just taken 20 minutes to write.

Wednesday, 26 September 2012

The Writing Revolution

It turns out that one of the key components of poor writing was, surprise surprise, poor literacy and poor understanding of features such as conjunctions and complex sentence structures. The school devised a regime where literacy skills were taught across the board, not just in English classes, with the outcome that learners were not just successful, they were more motivated overall.

So why write about this? Well, I could immediately see implications for my ESOL learners, and the way in which features such as conjunctions are taught. If you've ever picked up a bog-standard TEFL textbook, you'll probably know that basic things like 'and' 'so' and 'but' are dealt with in a relatively perfunctory style, and that more complex phrases such as 'even if', 'provided that', or 'rather than' don't make much of an appearance until Upper-Intermediate textbooks hove into view.

What if this is the wrong approach? I know from experience that the students who are most likely to go on to become really fluent users know how to handle relatively complex sentence structure, even from a quite low level of English, but that we shy away from teaching it as being 'too difficult'. Perhaps we should be encouraging students to actively engage with sentence complexity - after all, this is precisely what they would encounter in English out in The Wild, as it were. And in fact, by exposing them to these structures, we don't just help them with their writing, but also with dealing with texts - and we know from research that those who read more become more fluent. By teaching the different ways sentences can be constructed, we open the door to reading in English and thereby to greater confidence with handling the language overall.

It's also possibly a way to help students from certain cultural backgrounds with different literary structures and traditions to engage with the way that the English mind conducts arguments, debate etc.

Well, that's my take on it anyway. I'm going to have a little stab at it with some Entry 3 (pre-int to int) students and see what happens.

Monday, 24 September 2012

Padding on

To start with, I'm still impressed by the speed of the thing- it really is wonderfully responsive. I love how it renders pictures and documents- but this is all old hat. I can also see how it is extremely useful for carrying round large numbers of documents that you may need to access. Even the onscreen keyboard is pretty responsive- I'm managing to type this at almost normal typing speed, despite having to switch between keyboards.

What doesn't impress me is the fact that editing and text design are very cumbersome or nigh on impossible. I can edit a google doc in Cloudon, but the editing is done using a Word skin, and if I open the same document on the PC, I can't edit it straight away. This is annoying

, to put it mildly. I've also been trying out the video and audio capabilities of this thing, wondering whether they be good for embedding in our blended learning vile or as podcasts, only to run into the problem of Proprietory Formats. Why can't they be in .MP3 or .avi, or similar? Apple want us to share everything ( that's why it makes everything so easy to share), but only as long as everything is shared in the Apple Universe, rather than across universal formats. I'm also, being of a slightly older generation, somewhat wary of sharing my documents of dumping them in The Cloud- somehow it doesn't feel secure enough.

Anyway, back to more bread-and - butter issues -how useful is the iPad in class?

Answer so far - still Not A Lot. I can see direct uses in very small classes ( by which I mean one to one, or three or four students at most); I also think it has wonderful specialist applications for very young, very old, or infirm learners, or ones with Special Needs. I also used it with my five-year-old to practise writing the letters of the alphabet and simple spellings. Trawling the net for blogs and videos has proven rather uninspiring. Besides the tedious repetition, I end up coming across phrases such as, ' distribute your iPads evenly round the class....' Er, hello? Which planet do you live on? iPads? In an ESOL class? The only way that is going to happen is if the things get cheaper. A lot cheaper.

Yes, I can show videos by attaching it to a projector. Yes, I can store all my listening exercises on it, yes, I can project pages of work ya dah ya dah blah blah blah. But I can already do this anyway, and more importantly I can actually work with the materials rather than just gawp at them.

And that is my biggest bone of contention: this is mainly a device for consumption, not creation. It might be good for receptive skills in a limited way, but I really don't see how it is that much good for productive ones. In fact, I have my doubts about how efficacious it is for reading and listening. I get the feeling that the iPad is great for giving the illusion of permanence- a student might think that just because their learning is taking place on a nice shiny tablet, they are learning well, when in fact the opposite may be true - in fact, they are retaining less.

There was a piece of research a year or two ago that suggested making students learn from a blackboard factually made them learn better, especially if the teacher had scruffy handwriting. The speculation was that the visual 'roughness' made the brain work harder at deciphering what was written, and therefore the learner ended up retaining information better. When you look at an iPad, or indeed any other tablet, everything is wonderfully glossy. I'm worried it's all so well- varnished that anything presented on it wil, end up slipping off the learner's brain entirely.

Thursday, 20 September 2012

Alternative Grading Scales

Anyway, being an observer inevitably involves paperwork, and feedback. Oh, lovely feedback: that moment when someone smiles at you as you both sit down in a room lit by fluorescent strip lighting, smiles even more brightly and says, 'So, how did YOU think your lesson went?', the you say what you thought, and hope that you aren't going to get a Shit Sandwich* back.

A lot of these feedback sessions involve someone saying, 'on a scale of one to ten, how would you rate that?', or something similar. B.O.R.I.N.G.

I was thinking about this the other day, and started wondering whether you could scale things in a different way. After all, getting teachers to be imaginative can only be a good thing, right?

So why not ask them something like this?

'On a scale of monday morning to saturday night, how good was that lesson?'

When you start to think about it, this makes a lot of sense, in a leftfield kind of way. An observed lesson should, in theory at least, be a typical lesson - how the teacher delivers the class on average, rather than the manically prepared, coiffed, perfumed, shaven, dolled-up confection of a lesson that is the norm when you know that someone's coming in to take notes. I'd say, on this scale, anywhere between thursday at 11.30 a.m. and friday at 7 pm (with another bump on saturday between 1 and 6.30 pm) means it's a good lesson. Anything before thursday would be dull or below par; anything after friday 9.30 pm would be loud and overblown; and saturday at 3 a.m. would be a lesson that's hoiking kebabs into the gutter.

Anyway, I'm going to give this a try, and devise some for marking student essays.

Probably something along the lines of

'On a scale of Beaker from the Muppets to Animal, how incomprehensible is this essay?'.

*Shit Sandwich: the act of an appraiser giving you feedback where they start and finish with positive comments, filling the bit in between with a steaming pile of criticism, invective and bile, as in:

'Well, I liked your class file. Unfortunately, your lesson went down worse than a drunken whore, and you are, quite frankly, a stain upon the entire teaching profession. However, I was glad to see that you have a nice tie on.'

Monday, 17 September 2012

101 uses for an iPad in the ESL classroom

Sorry about the title if you were expecting yet another breathless blog about how iPads/tablet computers were about to totally revolutionise teaching FOR EVER. From what I can see, most of these over-excited breathless scrawls are either a) written by people who don't have much teaching experience, and think the iPad is going to do all the work for them, b) poorly written, with plenty of formatting and spelling mistakes because they've been written on an, uh, iPad, or c) they've been written by people who are being paid to flog all sorts of pap.

Well, I've been given an iPad as part of the college's experiemnt in using iPads in a Further Education environment. The trial is called the iPad Trial, amazingly enough, and has been going for the past year. From what I've witnessed so far, the iPad Trial seems to largely consist of wandering around with an iPad, occasionally using the notepad function to take notes. In other words, it's like having the world's fanciest, most expensive clipboard.

Having said that, I've been very curious indeed about the possibilities of using tablets in education, all the more so since it was announced that tablet computers have apparently outstripped the sale of PCs in the States. And I'm always happy to have my assumptions disabused or indeed smashed to bits and stamped on. So I was glad indeed to get hold of a nice, shiny, slightly used iPad and invited to go forth and trial it.

First thoughts?

My GOD, it's nice. It has a nice heft to it, although I don't think I'd like to cart it around in one hand all day. I love its tactility: using a keyboard even after just a few minutes of literally stroking the iPad felt odd. It's a sleek, purring pussycat covered in velvet and butter. I started off by uploading all the really important apps - Angry Birds, Temple Run, BBC iPlayer and the Guardian. And again, MY GOD, this is one fast machine, and the display! Awesome! It really does make your average pc or netbook look like a plodder.

So far, so typical reaction - there is no doubt whatsoever that the ipad is one handsome beast, and like anyone else who's ever picked one up, I felt a real WOW! moment.

Then I decided to put it through its paces, and think how I could use it in class.

My immediate thought was that it would be a supremely useful device on 1-to-1 classes, and for CALL lessons for learners who had little or no experience with PCs. For example, we have a group of retired Gurkhas in the college this year, and I could see how using a device that uses instinctive gestures to navigate rather than using a mouse would be enormously helpful. I could also see how I could carry round video and audio files, PDFs and documents for easy access in class.

The trouble is, how do these actually teach, and how do they do the job better than a desktop PC in class, or indeed, a piece of paper and a CD?

I then turned to the College Moodle VLE - it looks beautiful on screen, yes, but what's this? I can't edit or add anything, because of course iPads don't support certain things like Flash. So I can look, but I can't touch, as it were.

I tried downloading an app for editing files - it allows me to edit Google Docs as word or Excel files, but - what's this? - if I try to edit the same files on a PC, Google Docs won't allow me to - I can, again, look but not touch!

And that's the thing, so far: The iPad is wonderful to behold, but when it comes down to it, it's not very productive - not with the written word, anyway: The music and art apps seem to be much more promising. It is mainly a thing for consumption of content, not its production, and that concerns me somewhat in language learning - you can't have one and not the other.

It's also a somewhat solipsistic experience. The iPad, or tablets in general (or, for that matter, and somewhat ironically, smartphones) are essentially about the individual user. To make the whole iPad thing have a chance of working in class, every learner should have access to one - and that is unlikely to happen some day soon, not until prices crash significantly, and their capacity to be used for production increase.

I suspect that the real game-changer in terms of the use of tablet computers in education will be the new low-cost 7-inch tablets that have arrived on the scene - they're easier to carry, for starters, and they have the legs to do the things that you might need. If one of the manufacturers includes a stylus, you've got a product that is seriously usable in class.

Well, I've had the Ipad for a whole 5 days now, so maybe I'm still a bit prejudiced, and as I said at the beginning, I'm happy to be disabused of my notions. In the meantime, it still seems to me like a gorgeous clipboard. And something that's good as a cheeseboard.

Friday, 31 August 2012

That's handy!

Well, I've had a pretty good summer - largely involving travel, mountains, beaches, rain, lots of food and wine. And not a jot of study, work, students or anything resembling work.

No wonder I feel jaded after just four days back in the office. However, I can take advantage of the current lacuna before the students return to bring this blog back to life, and on to a subject I promised to bring up ages ago.

I am fascinated by the question of why some students seem to be so good at learning languages while others would lose a fight with an auxiliary verb. As a subject, it is one I keep returning to - what is the difference between the 'good' language learner and the 'bad' one? What do the 'good' ones do that the 'bad' ones don't? How can I make the 'bad' ones 'good'? Why is it that students get to an intermediate level of English, then the numbers who continue with their studies tail off?

Now, I have discussed some of this in previous posts - intermediate students hitting a wall, trying to motivate people through the tedious slog of learning, affective filters, the 'fuzzy' handling of language, discussion of whether there is such a thing as active and passive grammar and so on. All of these are part of this one question, of why some people learn languages so easily and others don't. The key, I suspect, may lie in my observation that language learners can function with limited language, but they do so in reduced, clumsy ways - what I term 'fuzzy handling'. For example, a learner will be able to express a request in the target language, but do so in a limited way, e.g. 'I want go to College. Are you know where is it please?', which works, but in a limited fashion - a native speaker would understand it, but wouldn't regard it as 'correct'.

OK, so far, so obvious. I've pointed out before that my intermediate students often continue to use language in this fuzzy way, and that a lot of language learning (and, of course, teaching) is about bringing the language into focus, to help the student use the target language in a precise, 'focused' form - in our example above, we'd be aiming to get the student saying 'Excuse me, I'd like to go to the college, but I don't know where it is. Could you tell me how to get there, please?', or something similar.

As so often happens, a possible answer to this issue struck me one night while doing something completely unrelated - you know, that 3 a.m. feeling when you suddenly wake up and know the name of somebody you've been trying to remember all day. Anyway, it all comes down to how we handle language, our dexterity with it, our......

...handedness.

Language use and learning displays handedness. That is, just as we have an innate preference to use one hand over another, so we do the same with language. If we are learning a new language, we can attempt to use it like our L1, but it will be in a limited way - just like trying to write with your left hand if you're right handed. In the case of beginning a new language, of course, it's as if you've grown a whole new hand and are trying to work out how to make it move. Imagine trying to do all the tasks that you normally do with your dominant hand with your non-dominant one - you can do them, but it feels awkward, odd, and clumsy - precisely how it feels when trying to use an L2 naturally.

OK, so what if you're ambidextrous? Or, in this case, someone with two or more birth languages? Well, bilinguals tend to show a preference for one language over another, or a preference for one for given situations, e.g. talking in on language at home but another with friends. Again, I would argue this shows evidence that language use displays handedness, a preference for use of language based on situation.

Well, what bearing does this have on language learning? I would argue that for some learners, especially monoglots, they have such strong handedness in their L1 that it hinders their ability to handle the new language, while others are more ready to experiment with their new 'hand', as it were. The latter are more prepared to experiment with the range of use - to reach out and 'feel' their way.

This explains why it's such a good idea to encourage learners to experiment with language use outside the classroom - the more they do it, the easier it becomes to use it.

And here's another argument in favour of handedness - people who learn a second language can sometimes perform a task in the L2 better than they can in their L1. For example, a colleague of mine lived in Mexico for several years, and while there not only learned Spanish, but also how to drive. She also bought a knackered VW Beetle that required numerous visits to the mechanic in order to keep it on the road. In order to describe to the mechanic what had gone wrong this time, she had to learn, rather quickly, the various ways of describing the thing and what had fallen off, gone 'booinng' or had exploded. In fact, she became rather good at this, and bartering the price down with her mechanic for parts and labour.

But can she do the same here in the UK, in English? Nope, not without difficulty anyway, as she lacks the vocabulary to describe the things that drop off, go 'booiing' or explode. However, were she to discover a Mexican mechanic, she'd breeze through. In other words, for a specific situation, she is showing preference, or handedness, to a particular language - just as you might prefer to use your left hand to change gears on a car while steering with the right (if you live in a country like the UK where you drive on the correct side of the road, i.e. the left :) ).

I'm not going to write much more on this subject at the moment, as it merits more than a blog entry, but I will say this - thinking about language and handedness has lead me on to something else about how we acquire our L1s in the first place. But more about that in a later blog post.

Monday, 23 July 2012

Motivation...

Nothing. Nada. Zilch. Not a sausage. Not even a small pork chipolata on a cocktail stick.

Well, actually, I have in some ways done quite a lot, but it's all the little stuff - checking off records of work, trimming schemes of work for the coming academic year, updating course handbooks, completing records of achievement for the exams, writing reference letters - all the bread and butter stuff, and none of the exciting zingy contents that should be in the Grand Sandwich of Language Teaching. It is not, as you know, very motivating, yet it has to be done, because without all the planning and admin, there is simply no learning or teaching or all the parts that still make this job interesting.

Which leads me on to the point of this post: How do we keep learners motivated when they're doing the boring bits of learning a language? In fact, what parts of language learning do learners consider tedious? Going back into my own murky language learning past, I would say that, while learning French, I found learning all the irregular forms annoying, as well as gender agreement - but this in part was because these had not been sufficiently explained by the teacher(s). It was also hard work, being in a class of 30 other students, listening to a half-mad tutor rave on about the beauties of French, while being taught to say 'Where is my monkey? My monkey is in the tree' , or listening to a tinny little tape recorder say 'Ecoutez et repetez....'

However, when I was learning Turkish, I found it a challenging, but enjoyable experience, most probably because 1) I was teaching myself , 2) I found I could master a foreign language after years of hearing 'Oh, the British are useless at foreign languages' and 3) I felt a sense of competitiveness with other Turkish-speaking Brits - who could say something better, or find new words faster? I only found it hard work after reaching a high level of spoken and everyday written fluency, when I started trying to use more formal language and structure, and discovered that it was almost like learning a brand new language. It was very frustrating indeed, and still is. But, with practice and study, I'm sure I'll be able to master it entirely.

Sounds familiar? So it should. I think a lot of students just lose motivation when they realise that they have to get on with the slog of learning, simply because it feels like they're doing nothing and there are few immediate results. Remember, English is an easy language to speak basically (or, as my student and well-known Brazilian playwright Antonio Rocco said to me, 'English is the easiest language to speak badly'), meaning that even after a little work, a learner can perceive sudden leaps and bounds in their knowledge and use of the language. It's only later that everything seems to slow down, and the miracle of suddenly perceiving and using another tongue gets dragged down into the mundane. How do we keep students keeping on at it?

Well, that's my question for you. I'm off for the summer.

Thursday, 12 July 2012

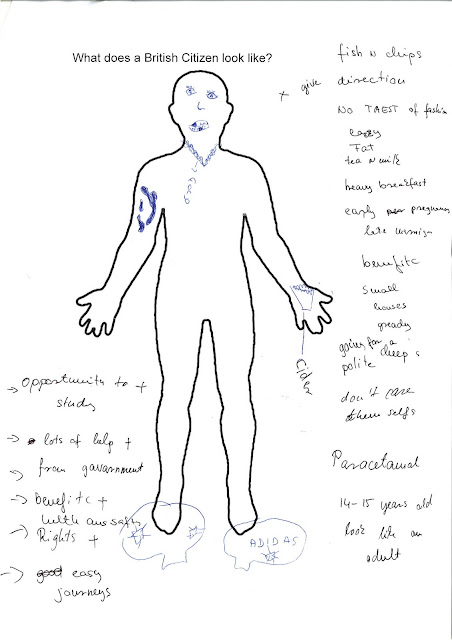

What does a British Citizen look like?

Like most teachers, by the end of the year I generally require the services of a team of industrial archaeologists to sift through the varying strata until the desk surface is reached. However, thanks to two moves of office location in as many years, each of which involved boxing LOTS of stuff up and conflating the debris of desks in two locations, this supposedly annual process had been delayed until this year. You can probably imagine the towering bundles of dreck, clouds forming at their pinnacles, while seabirds try to nest amid bundles of yellowing homework and unused photocopied resources. Well, after calling in Time Team, and then setting the braziers burning, I have been left with a desk that looks more like a working space, plus neatly organised resources and a few choice samples of student work, all ready for the September onslaught, when paper will once more accrue on on my desk faster than autumn leaves in a storm.

So what the hell has this got to do with the title of this post? I thought I'd share a sample of the aforementioned student work with you. When I'm wearing my ESOL teacher hat, I have to include the topic of Citizenship in the class work, as this is a requirement of ESOL classes in FE - it means that students learn about stuff like MPs, Human Rights, the UK legal system, a bit about history, and generally practical stuff that helps them live here. And because they study it over the course of a year, it means that they don't have to do the ghastly citizenship test, an exam that would ensure about 70% of the native population were kicked out of the country, so obtuse it is.

One of my first Citizenship lessons is a discussion about what it means to be a British citizen. This is a very useful exercise, because it means students can discuss stereotypes, habitual behaviour, and differences between life in their own countries and here - linguistically and thematically a very rich seam. I get students into working groups initially to discuss some questions on a worksheet, then lead a whole class feedback. After this, I give groups a sheet. On this sheet is an outline of a human body, and the question, 'What does a British citizen look like?' I then instruct the students to work in their groups and draw what they think a British citizen looks like and write a few phrases.

Now, the whole idea of this is that it's meant to show that British citizens come in all shapes and sizes, that there's no such thing as a 'typical' citizen, that it doesn't matter where you're from, that we are a pluralistic, cosmopolitan society that can rise nobly above crude stereotypes and see The Person Within.

Do you think that is what the students had in mind as well?

Oh dear, no. Instead, most students end up drawing and describing what they think a typical native British person looks like. Here are a few:

|

| OK...not too bad... |

|

| well, at least this one's polite... |

|

| Hmm - Reading town centre on a friday night |

|

| WHAT? |

|

| ! |

Tuesday, 3 July 2012

Getting back in the saddle

Well, I have been neglecting things somewhat, thanks to my lovely, lovely DELTA course, amongst other things. That's the trouble with doing a Dip: you're so busy learning how to be a brilliant teacher that you, er, stop teaching properly, and head back to good ol' Headway, page 76.

Well, the studying is finished for now, although I've been given th go-ahead in my institution to pilot a course based on my module 3 course design - a blended learning course using a Flipped Class Model with TBL in the class-based sessions. I'm experimenting with the online materials at the moment, but unfortunately I'm slightly hindered thanks to our Moodle VLE being updated.

Now, you might think that this flies directly in the face of what I wrote in my last post, but in fact it's a direct development from the principles of using tech that I laid out. This will be a pilot project, which will give me data on the efficacy or otherwise of blended learning. I will initially try it on a limited group of students who have previously been identified as being relatively digitally literate, and on teachers who don't react to computers with gibbering fear. Once I've got some more work done on it, I'll give a fuller report.

Friday, 16 March 2012

Brand New, Shiny New, Shiny Brandy New Tech in class: Worth it?

You couldn't be more wrong.

All I see is a hopeless mishmash of poorly joined-up enthusiasm with little actual thought of what it entails practically and pragmatically.

Let's start with the most fundamental of all - access. Not every student can afford an ipad, or an Android-driven tablet, or even a smartphone. Believe it or not, some students, especially older learners, don't even want a smartphone, or a tablet - and some find using computers difficult. Does this make them losers who don't deserve to learn? Hell it does. If learners are not at least beginning their learning from a level playing field, then neither true learning can occur, nor can the teacher honestly say they are teaching - all they are doing is playing at teaching.

point two: materials. The major publishers have, as we know, taken quite a long time to latch on to how e-materials can be produced. Some more tech-savvy teachers have produced decent materials that work on a variety of platforms, but even so, what is out there is horribly uneven in terms of quality and, pace the first point, accessiblilty. Currently, if any teacher is truly serious about offering equal opportunity of learning to all their learners, they need to have (near-) identical materials available online, as an app, in pdf, as a .doc or equivalent and as a good old bit of paper.

point three: just because we, as educators, get excited about a new piece of tech or a new website or whatever, it does not necesarily follow that a) our students will be equally excited or b) that the brand new shiny thing we have discovered is actually, genuinely useful or game-changing in the class. We might love Twitter or Vimeo or whatever, but unless we consider how pragmatic it is to use it, and how often, it is far too easy to overindulge ourselves to the detriment of learning - but because we're using the new tech or website, we can convince ourselves taht actually we're teaching well, or the students are learning well!

I'd like to suggest a few points that anyone who is getting excited about new tech/software should think about.

1) What does this do that the old method doesn't? If the answer to this is 'nothing' or 'I don't know', then don't use it. Either work out how it is different, or leave well alone. This applies to websites, software and hardware.

2) What does this do better than the old method? Answer as above, really

3) Will my learners benefit from some discovery that excites me? If the answer is 'no', the leave it out of class.

4) Do my learners have access to this online resource I want the class to use? If they don't, then you are the one disadvantaging them. Rethink your approach.

5) Can my students afford this piece of tech? If the answer is 'no', then why are you basing your lesson around it?

One thing I have noticed amid all the excitement over tablet technology - the students I have don't have tablets, but they are quite avid users of smartphones. However, it is glaringly obvious from their use that they see them as accessories to learning rather than necessarily portals for learning - in fact, they browse language sites and apps rather than rely on them. This is an important thing to note, as it means that they have do with language apps on their phones what they naturally do with the other software on it - use it in a casual, relaxed way. If I made them use their phones in a more concentrated 'LEARNING-STYLE' way, they probably wouldn't use them as effectively. Instead of making dedicated learning-rich apps, it might be better to create ones that encourage and support the natural way people browse their phones for information.

Tuesday, 28 February 2012

Now Podcasting!

And then I realised that trying to explain an idea in four minutes or thereabout requires spare, accurate conciseness, and that made me consider how I give explanations in class, especially as it took me ages to think about what I wanted to say, how to say it, and whether my explanation was sufficient enough.

Anyway, here it is: Paul's English Podcasts. Judge for yourself. It is still early days yet, so I'm sure I can get better!

Monday, 23 January 2012

mondaaaaaaaaaaay, part two

Imagine someone is coming to visit Reading for a couple of days. Where can they stay? What can they do?

We brainstormed a few suggestions, then I told them to whip out their smartphones and research things to do in Reading, places to stay, restaurants etc, organising them into groups of 3/4. They wrote their ideas down on flipchart paper, and, with minimal intervention from me, researched and organised their ideas. They then presented these to the other groups, and the class as a whole voted for the best places to stay, eat in, go to etc.

Good, eh?

It didn't finish there. While they were doing that, I went to Page O Rama, and set up a web page, which I then added to the college intranet for all to gawp it. It isn't finished yet, but the whole lesson finished with a satisfying zing.