Well, that was a great conference! Packed to the rafters with delegates and good ideas. I found it really refreshing to escape the purlieus of my normal work existence and catch up with a group of fellow professionals.

Obviously, I couldn't see all the presentations, so I look forward to catching up on a few on the English UK website later on. I enjoyed Russell Stannard's talk on tech to enhance student talking, and Hugh Dellar's Counter-Blast to the sloppy use of technology in the class.

Here's my presentation from The English UK teachers' Conference 2013, along with a video about the flipped class and a sample Google form underneath. Here's a link to Socrative, the synchronous class-based quiz tool I mention in the presentation.

I'll be adding a few more links to tools I've used for blended and flipped learning that you may find useful.

and here's a short introduction to the Flipped Class...

Studies, theories, ideas, notes from the workface and occasional bits of stupidity.

Friday, 8 November 2013

Monday, 28 October 2013

English UK beckons again..

It looks like I'm headed for the English UK Teachers' Conference once more, although I have to say it is with somewhat mixed feelings.

Unfortunately, Dave Willis has passed away, and the organisers have asked me to step into the not inconsiderable breach with my own proposal. I'll be talking about Blended Learning and Flipped Classrooms, and in a nod to Dave and Jane, I'm hoping to include something about TBL in a blended learning environment as well.

Unfortunately, Dave Willis has passed away, and the organisers have asked me to step into the not inconsiderable breach with my own proposal. I'll be talking about Blended Learning and Flipped Classrooms, and in a nod to Dave and Jane, I'm hoping to include something about TBL in a blended learning environment as well.

Monday, 21 October 2013

Full Circle

There were only a few minutes left. I stared at myself in the mirror, trying to gee myself up, but I felt a horrible twisting in my guts. They were waiting for me.

I'd spent the better part of the whole day getting ready, looking at what material I had, and trying to think out my strategies. Several draft plans had ended up scrunched in a bin, and I had gone through a packet and a half of cheap cigarettes. In the end, I thought I'd made something that would get me through. It had a beginning, a middle and an end. It did, or should do, what it said on the tin, as it were. My train of thought hadn't been helped by the fact that I'd been fighting several issues all day. The first was a hangover, caused by watching Galatasaray draw a match with Manchester United the night before, leading to celebrations the size of which I'd never experienced before. The second issue was the noise from the street. I had never really encountered such pervasive, incessant noise pollution before, from gas vans with jingles that sounded like ice cream vans to fishmongers screaming their wares, from insanely loud music in passing cars to streets full of people calling, shouting, selling, announcing. However, I felt, finally, that I was ready.

I picked up my plan and headed off.

As I walked towards my destination, however, I felt my certainty and confidence drain away, leaving nothing but doubt. I arrived, but with half an hour before my fateful assignation, I locked myself in the bathroom, looked at myself, and said out loud,

'What the fuck am I doing here teaching English?'

There was nothing for it however, but to go forth, open the door, and be introduced to fourteen polite, smiling faces. I took a deep breath, and said, loudly,

'Good Morning!'

It was seven in the evening.

And so began my career in TEFL. My first real lesson, on the 21st October, 1993. Here's the page I used:

Good Old New Cambridge English Course, Book 1, Unit 9c, 'I look like my father'

How I managed to stretch this over an hour and a half of teaching, I have no idea. Yet it has stuck vividly with me, simply because it was that very first lesson. I remember about half the class as well: Mustafa, Umut, Tolga, Cigdem, Esra, Muge, Ibrahim, and Pinar. They were all aged 18-24, so not much younger than me, really.

Since then, I've taught literally thousands of students, and covered virtually everything. My first three years of lesson were mostly at elementary and pre-intermediate level, using the above book and the original Headway series, to the extent that I can still quote large chunks of the tapescripts, complete with the actors' dodgy 'foreign' accents (e.g. 'I live in Tex-ass. That's the secon' biggest state. I got fourteen-fifteen bedrooms...'). I have taught TOEFL prep, and experience I'd rather avoid doing again, thank you very much. Later, I progressed to the dizzy heights of Intermediate level classes, and slowly progressed upwards to do, once I came back to the UK, FCE, CAE and CPE groups, as well as International Foundation Programmes and ESP courses. I've taught EFL and ESOL and the shades in between.

I've been a DOS. I've been Course Leader and Programme Leader. I've been a presenter at conferences, and delivered CPD to colleagues.

And where do I find myself now? After all the cuts to FE spending and funding, after several OFSTED inspections where Leadership and Management have been slated, but nothing has changed, after my team has been butchered to just 2.7 Full Time workers?

I'm teaching an elementary class and a pre-intermediate course. And after years of teaching just high-level students, I've remembered what kept me going in those first couple of years: A student's eyes light up because they'd said something accurately for the VERY first time, or they'd worked out a concept and could apply it straight away, that magical moment of comprehension. You can get it at higher levels, but there's a visceral shiver of excitement from seeing it happen with someone for the first time ever, and use it straight away.

So today, with my Entry 2 (CEFR: A2-B1; EFL equivalent: Elementary) ESOL group, I taught the page above.

It was RUBBISH.

I brought it to a quick end, and carried on with something brilliant instead.

I'd spent the better part of the whole day getting ready, looking at what material I had, and trying to think out my strategies. Several draft plans had ended up scrunched in a bin, and I had gone through a packet and a half of cheap cigarettes. In the end, I thought I'd made something that would get me through. It had a beginning, a middle and an end. It did, or should do, what it said on the tin, as it were. My train of thought hadn't been helped by the fact that I'd been fighting several issues all day. The first was a hangover, caused by watching Galatasaray draw a match with Manchester United the night before, leading to celebrations the size of which I'd never experienced before. The second issue was the noise from the street. I had never really encountered such pervasive, incessant noise pollution before, from gas vans with jingles that sounded like ice cream vans to fishmongers screaming their wares, from insanely loud music in passing cars to streets full of people calling, shouting, selling, announcing. However, I felt, finally, that I was ready.

I picked up my plan and headed off.

|

| me heading bravely off to face the action. |

As I walked towards my destination, however, I felt my certainty and confidence drain away, leaving nothing but doubt. I arrived, but with half an hour before my fateful assignation, I locked myself in the bathroom, looked at myself, and said out loud,

'What the fuck am I doing here teaching English?'

|

| Oh well, who wants to live forever! TEEAAACCCHHHHH!!!! |

There was nothing for it however, but to go forth, open the door, and be introduced to fourteen polite, smiling faces. I took a deep breath, and said, loudly,

'Good Morning!'

It was seven in the evening.

And so began my career in TEFL. My first real lesson, on the 21st October, 1993. Here's the page I used:

Good Old New Cambridge English Course, Book 1, Unit 9c, 'I look like my father'

How I managed to stretch this over an hour and a half of teaching, I have no idea. Yet it has stuck vividly with me, simply because it was that very first lesson. I remember about half the class as well: Mustafa, Umut, Tolga, Cigdem, Esra, Muge, Ibrahim, and Pinar. They were all aged 18-24, so not much younger than me, really.

Since then, I've taught literally thousands of students, and covered virtually everything. My first three years of lesson were mostly at elementary and pre-intermediate level, using the above book and the original Headway series, to the extent that I can still quote large chunks of the tapescripts, complete with the actors' dodgy 'foreign' accents (e.g. 'I live in Tex-ass. That's the secon' biggest state. I got fourteen-fifteen bedrooms...'). I have taught TOEFL prep, and experience I'd rather avoid doing again, thank you very much. Later, I progressed to the dizzy heights of Intermediate level classes, and slowly progressed upwards to do, once I came back to the UK, FCE, CAE and CPE groups, as well as International Foundation Programmes and ESP courses. I've taught EFL and ESOL and the shades in between.

I've been a DOS. I've been Course Leader and Programme Leader. I've been a presenter at conferences, and delivered CPD to colleagues.

And where do I find myself now? After all the cuts to FE spending and funding, after several OFSTED inspections where Leadership and Management have been slated, but nothing has changed, after my team has been butchered to just 2.7 Full Time workers?

I'm teaching an elementary class and a pre-intermediate course. And after years of teaching just high-level students, I've remembered what kept me going in those first couple of years: A student's eyes light up because they'd said something accurately for the VERY first time, or they'd worked out a concept and could apply it straight away, that magical moment of comprehension. You can get it at higher levels, but there's a visceral shiver of excitement from seeing it happen with someone for the first time ever, and use it straight away.

So today, with my Entry 2 (CEFR: A2-B1; EFL equivalent: Elementary) ESOL group, I taught the page above.

It was RUBBISH.

I brought it to a quick end, and carried on with something brilliant instead.

Wednesday, 18 September 2013

Faking it.

Right, now that I'm back into the maelstrom of the new term and put a few lessons under the belt, time to kickstart the old blog again - I hope you all had a good summer, readers.

I don't know about you, but I still feel somewhat apprehensive before going into a new class, even after twenty years before the whiteboard. I still remember my first time going into a class for real, staring in panic at my reflection in the mirror of the bathroom I'd locked myself in, saying 'OhshitohshitohshitwhatthebloodyhellhaveIgotmyselfinto?' and trying to breathe. I just wanted to run away, but knew I couldn't. I would, eventually, have to unlock the door and go into that classroom to be met by twenty pairs of eyes. Minutes passed, and I kept on looking at myself, trying to chide my reflection into action. Suddenly, the school bell, an electronic little jingle that kind of went all wonky at the end, sounded:

Bing bang bing bang bing bang biiioooononinining.

This was it.

What did I do?

I went on to teach for the next twenty years, by striding into the class and saying, as loudly as I could without shouting, 'Good Evening!'

And I've been doing varieties of this with every new class ever since. It was all about faking it at the beginning - the impression of control, the sense of being the boss of the environment, until I actually became so. That may make me sound as if I need to have the class centred around me, and I think in retrospect that was what the first few years of my career was about, but until I learned to master what I do it was where I felt more comfortable. So, I faked it until I became it, which neatly segues into a mention of Amy Cuddy's TED Talk Presentation on that very subject. In it, she talks about how adopting power poses, i.e. postures that imply confidence and dominance, even for as short a time as two minutes, actually change the way a person thinks of themselves, and of how they perform in situations such as interviews. She has conducted experiments that strongly suggest that how we hold ourselves physically strongly feeds into our mental health and general wellbeing, and I'd recommend giving a view.

So, why am I mentioning this? Well, because as a seasoned TEFLer ready to jump on any passing idea as a teaching opportunity, it got me wondering whether I couldn't experiment on this with my own students. The premise: What if adopting 'power poses' would actually improve a student's capacity to learn English? Teaching ESOL students as I do, it struck me that an awful lot of our learners do actually hold themselves in class in rather diminutive, submissive positions - in the role, as it were, of supplicants before the Grail Of Language Learning. In addition, people with their Affective Filters set to Stun tend to adopt highly defensive postures. What if making the learners sit in ways that imply confidence actually changes their attitude and ability, and actually boosts their learning capacity? This would also, incidentally, link into a subject I've discussed here (and at the EUK conference) before, namely Maslovian Hierarchies and Thematically linked language learning.

Well, we'd have to design an experiment to see if it could work, and I think I may have an opportunity to give it a test- but more of that in another post.

I don't know about you, but I still feel somewhat apprehensive before going into a new class, even after twenty years before the whiteboard. I still remember my first time going into a class for real, staring in panic at my reflection in the mirror of the bathroom I'd locked myself in, saying 'OhshitohshitohshitwhatthebloodyhellhaveIgotmyselfinto?' and trying to breathe. I just wanted to run away, but knew I couldn't. I would, eventually, have to unlock the door and go into that classroom to be met by twenty pairs of eyes. Minutes passed, and I kept on looking at myself, trying to chide my reflection into action. Suddenly, the school bell, an electronic little jingle that kind of went all wonky at the end, sounded:

Bing bang bing bang bing bang biiioooononinining.

This was it.

What did I do?

I went on to teach for the next twenty years, by striding into the class and saying, as loudly as I could without shouting, 'Good Evening!'

And I've been doing varieties of this with every new class ever since. It was all about faking it at the beginning - the impression of control, the sense of being the boss of the environment, until I actually became so. That may make me sound as if I need to have the class centred around me, and I think in retrospect that was what the first few years of my career was about, but until I learned to master what I do it was where I felt more comfortable. So, I faked it until I became it, which neatly segues into a mention of Amy Cuddy's TED Talk Presentation on that very subject. In it, she talks about how adopting power poses, i.e. postures that imply confidence and dominance, even for as short a time as two minutes, actually change the way a person thinks of themselves, and of how they perform in situations such as interviews. She has conducted experiments that strongly suggest that how we hold ourselves physically strongly feeds into our mental health and general wellbeing, and I'd recommend giving a view.

So, why am I mentioning this? Well, because as a seasoned TEFLer ready to jump on any passing idea as a teaching opportunity, it got me wondering whether I couldn't experiment on this with my own students. The premise: What if adopting 'power poses' would actually improve a student's capacity to learn English? Teaching ESOL students as I do, it struck me that an awful lot of our learners do actually hold themselves in class in rather diminutive, submissive positions - in the role, as it were, of supplicants before the Grail Of Language Learning. In addition, people with their Affective Filters set to Stun tend to adopt highly defensive postures. What if making the learners sit in ways that imply confidence actually changes their attitude and ability, and actually boosts their learning capacity? This would also, incidentally, link into a subject I've discussed here (and at the EUK conference) before, namely Maslovian Hierarchies and Thematically linked language learning.

Well, we'd have to design an experiment to see if it could work, and I think I may have an opportunity to give it a test- but more of that in another post.

Tuesday, 23 July 2013

Time for a summer blockbuster

Ah, summer...long days away from work, sweltering temperatures outside, cool drinks, time to loaf around and catch up on all that reading you've promised yourself and de-stress from the 9 to 5 (or 9 am to 9 pm in my case on thursdays).

And time to go to the movies and watch something noisy involving explosions and car chases and stuff. There are few guilty pleasures better than a trashy summer blockbuster.

The problem is, I end up with the feeling that I've seen one, I've seen them all.

And do you know, that's probably the case - almost all the big budget action movies are written to a series of simple guidelines.

I read a very interesting article on Blake Snyder and his book Save the Cat! The last book on screenwriting you'll ever need, which outlines 15 points you'll find in your typical successful blockbuster.

Here they are:

And time to go to the movies and watch something noisy involving explosions and car chases and stuff. There are few guilty pleasures better than a trashy summer blockbuster.

The problem is, I end up with the feeling that I've seen one, I've seen them all.

And do you know, that's probably the case - almost all the big budget action movies are written to a series of simple guidelines.

I read a very interesting article on Blake Snyder and his book Save the Cat! The last book on screenwriting you'll ever need, which outlines 15 points you'll find in your typical successful blockbuster.

Here they are:

- Opening image

- Theme is stated

- The set-up

- The catalyst

- Debate

- Break into act II

- B-story

- Fun and games

- Midpoint

- Bad guys close in

- All is lost

- Dark night of the soul

- Break into act III

- Finale

- Final image

Go and watch a blockbuster from the last decade or so, and you should be able to spot all of these moments.

So, why on Earth am I talking about screenwriting guidelines on my ELT Journal blog?

Because it struck me that you could, with a little bit of flexibility, apply these same principles to lesson planning. Certainly the Dark Night of the Soul bit, which usually hits me about three quarters of the way through a lesson on Present Perfect.

I'm not sure about the Bad Guys close in, though. I suppose it could be something like Bad Grammar Appears.

However, the idea of opening and closing images, the statement of aims, the catalyst for action, the B-story and certainly fun and games are all features that we could recognise in any given lesson.

Anyway, just to avoid poaching, I'm patenting, trademarking, copywriting and all-rights-reserving this as The Blockbuster Approach © ™ to ELT.

Because of course what the world needs is another ELT methodology.

Have a very good summer, one and all.

1

Labels:

approaches,

blockbuster,

elt,

Methodology

Thursday, 30 May 2013

What makes a successful lesson?

I've just been reading 'The Map Is Not The Territory' over on The Secret DOS's blog, which discusses the efficacy (or not) of lesson planning. Speaking as someone with over 20 years' experience of EFL, I can say my relationship to prepping for classes has waxed and waned over time, and involves several variables, including:

- in the early years, not having any experience at all, leading to the creation of exquisitely immaculate lesson plans, taking hours of artisanal labour and minutes of actual lesson time

- the amount of paper available to write down (this was pre-pc) an LP. Several of these were literally created on fag packets.

- being observed/inspected/gang-probed by OFSTED, leading to monumental edifices of LPs

- knowing the materials and class so well that it feels like a waste of time to create an LP

- pretending to be investigating Dogme ELT and saying stuff like, 'Ha! The LP is ANATHEMA to Teaching Unplugged!'

- Hangovers.

I am, of course, writing slightly tongue-in-cheek, he said, slipping in a disclaimer for the benefit of future employers.

However, The Secret DOS's article got me thinking - what does make a successful lesson? We've all had lessons that we've prepared to the finest edge of perfection, but which in class fly in very much the same way that a heavy brick doesn't; Then again, we've gone into a lesson without so much as a really badly-photocopied worksheet in lieu of preparation, and ended up having something incredibly productive.

The trouble is, it's hard to empirically demonstrate exactly what it is that makes a given lesson successful, as there are so many variables.

I thought I'd give it a go, though, using the Power Of A Popplet.

I've had to strip out some variables, such as Will To Live Sapped By The Fact It's Thursday Afternoon, but I've kept the salient ones in. Having said that, I've also probably missed a few as well, but seeing as I started this as a bit of fun, I actually think I've ended up with something useful.

So, tongue now firmly planted in cheek, does this mean we can create an equation for a successful lesson? Let's give it a try:

Ls = Ti{Texp(yt+knCl/knMat) +Lp+Ei+M/TintM} + Si{Skn(knCl/unCl+unInst+knBhvr+knT/Cl)+i(t/cl+mats)+FcX+Sint}>0

where Ls= Lesson Success, and Ti (teacher input) plus Si (Student input) is greater than 0.

Of course, I now expect this equation to appear as gospel truth in the Daily Telegraph.

What do you think? Have I missed anything?

If the Popplet doesn't for some reason appear above, here is the first draft as a pic:

Tuesday, 21 May 2013

ESOL and Digital Literacy in my college

I've been 'attending', if that's the right word, the Virtual Round Table Web Conference this weekend, although I couldn't participate as, such as I would have liked due to other commitments. If you haven't heard of it before, it's an annual conference on language learning and online technology, and how we can integrate the wonderful world of IT ever more deeply into the teaching and learning process. There were some excellent presentations and debates, but if you wanted to start off anywhere, I think I'd have to recommend Gavin Dudeney and Nicky Hockley's presentation on Digital Literacies, an area which is has far wider implications for education than just language learning.

Anyway, it got me thinking about how we use digital literacy and e-learning with our ESOL students, and where we'd like to take it in the future. I thought I'd give a snapshot of the situation in my workplace and what we've experienced/discovered.

We currently use Moodle as our VLE. in previous years, we had Blackboard, then migrated to Moodle a couple of year back. Unfortunately, it was a rather dodgy iteration of the software, and really quite glitchy - things wouldn't save, uploading materials took ages, and there was little attempt at encouraging learners to use it. Where it was used, it was frequently as a repository for word, excel and pdf documents - in other words, as nothing ore than a glorified filing cabinet gathering digital dust. Teachers didn't trust it, didn't understand it, and didn't use it. Combined with a server that was temperamental and a college wireless network that would throw hissy fits at unexpected intervals, and you can understand why it was all a bit unloved.

However, in summer 2012 we installed the latest iteration of Moodle, and I set about experimenting and installing course areas for ESOL. Rather than set up a separate course for each class, I decided to keep it relatively simple, and establish a learning area for each level, e.g. ESOL E1, E2 etc. This meant that the learners (and the teachers) could share materials quite easily and I felt it might foster greater group interaction. We also had a regular 45-minute IT room slot in the teaching schedule for each group, along with an easier way to access Moodle from home, plus an increase in the number of available PCs around the college.

Here are some of the key things that we have found from this setup:

Anyway, it got me thinking about how we use digital literacy and e-learning with our ESOL students, and where we'd like to take it in the future. I thought I'd give a snapshot of the situation in my workplace and what we've experienced/discovered.

We currently use Moodle as our VLE. in previous years, we had Blackboard, then migrated to Moodle a couple of year back. Unfortunately, it was a rather dodgy iteration of the software, and really quite glitchy - things wouldn't save, uploading materials took ages, and there was little attempt at encouraging learners to use it. Where it was used, it was frequently as a repository for word, excel and pdf documents - in other words, as nothing ore than a glorified filing cabinet gathering digital dust. Teachers didn't trust it, didn't understand it, and didn't use it. Combined with a server that was temperamental and a college wireless network that would throw hissy fits at unexpected intervals, and you can understand why it was all a bit unloved.

However, in summer 2012 we installed the latest iteration of Moodle, and I set about experimenting and installing course areas for ESOL. Rather than set up a separate course for each class, I decided to keep it relatively simple, and establish a learning area for each level, e.g. ESOL E1, E2 etc. This meant that the learners (and the teachers) could share materials quite easily and I felt it might foster greater group interaction. We also had a regular 45-minute IT room slot in the teaching schedule for each group, along with an easier way to access Moodle from home, plus an increase in the number of available PCs around the college.

Here are some of the key things that we have found from this setup:

- Probably the single most successful thing on Moodle is the use of forums and chats. Our Entry One learners, for example, are producing work not only more prolifically, but more accurately. Learners' written output has increased by at least 100%, and they are happy to access the VLE from home. The use of fora does vary from class to class, but in many ways this is dependent on the teacher's attitude towards using it.

- The clearer the layout, the more likely the students are to use it. Just like a good coursebook, design is vital to engaging the learners' interest. I've been experimenting with various styles and layouts throughout the year, and the most useful way of getting higher usage rates is by using photos/pictures with hyperlinks to other areas and exercises. It also makes Moodle much easier to use if you're accessing it via tablets/mobiles.

- Some teachers are still frightened that they are going to break the whole Internet by doing something wrong on Moodle. I'm helping to work on that one. Students pick up on teachers' attitudes, and we really have to ensure that the instructors are digitally literate.

- students do want to engage with IT, but sometimes they lack either the equipment, the time, or the knowhow (and sometimes all three) to use it. having the 45-minute slot may seem minimal, but it acts as a vital gateway for our less digitally-literate learners - and some of the teachers, too.

- as learners increase their language knowledge, they engage more with digital literacy. It's striking how the higher the class level, the more likely that students use their mobiles to support learning, for example. This is actually a bit odd - why should your language ability have any impact on how you use IT?

- students are very wary of creating non-written output, e.g. voice recordings or video. To be honest, this may be because the teachers themselves are wary, or worried that they may have to spend inordinate amounts of time helping the learners upload stuff. Something I hope to tackle in the future.

well, that's a few things I've noticed here. As to the future, I'm aiming to create much more of a blended learning experience using Moodle across the board, plus some specialised near-autonomous learning modules in Academic English, and, specifically for ESOL, a Citizenship course. The question remains about how to fully engage both instructors and learners into using IT more efficiently.

Thursday, 16 May 2013

Finding the Right Blend(ed lesson): Creating or Curating the Content?

I've been up to my eyeballs in using Moodle in my college since September, and working out different ways to blend learning from the screen to the classroom. One issue that I find, and I'm sure others do too, is creating my own content for online use. Sometimes, I just want to sit my learners down and give them something that'll work right out of the tin, but when I go Googlewhacking various ELT/ESL sites, I find so much that I get overwhelmed.

The question is this: should we create our content or curate it from a variety of different sources?

On the face of it, creating the content should be what we do - we know our learners, we understand their needs, and we should tailor our materials to fit their requirements. Any teacher with sufficient experience can make things for the class, and make them well. The problem, however, is TIME. When do you have enough of this precious commodity to actually sit down at a keyboard, sketch out your ideas and develop interactive content? Also, there is the issue of the amount of time it takes to create and the amount of time it takes to actually use the resource. I once spent about three hours lovingly crafting something, only to get completely deflated when my learners banged through it in five minutes flat. And if you're not confident with your IT skills, it adds another obstacle to making efficient online content. The other thing to consider is that you want to make content that can be used again and again, not just as a one-off. What's the point of spending an hour making something for five minutes of student interaction?

So what about curating the content? We do this all the time with our classroom materials after all - we get our textbooks and resource books, choose what we feel will be most useful for the learners, and deliver it. Simple. The trouble with online content however, is that a) there is SO MUCH of it and b) a lot of it is poorly-designed, or has weak content, or doesn't actually lead anywhere. There are literally millions of sites that do gap-fills, or have a little video with a little task, or wordsearch puzzles, but I sometimes wonder what the LEARNING point is. You also have to consider how the online content 'fits' into the lesson, or how it can be embedded into your VLE. It's possible to find all the content you need and send it to your learners as a list of links, but from my experience, appealing visual content, delivered in a context-based environment, e.g. in a course page on Moodle, is most effective.

As ever, it's probably best to compromise, at least at the beginning. Creating your own content is time-comsuming, but once it's done, it's done - for good. Here are a few points to consider:

The question is this: should we create our content or curate it from a variety of different sources?

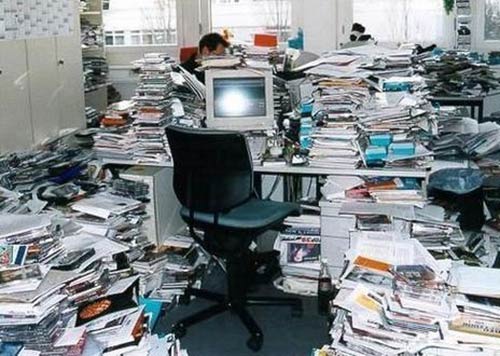

|

| right idea, wrong method? |

|

| I know I'll find an easy 5-minute exercise in here somewhere.. |

As ever, it's probably best to compromise, at least at the beginning. Creating your own content is time-comsuming, but once it's done, it's done - for good. Here are a few points to consider:

- start off with the scheme of work for the year/term. what content can best be delivered online, and which should stay in class? how do the two types of learning interact with each other?

- which content could be most efficiently created by you for online content? Consider things that you do again and again - for example, certain types of input (for me, this might be explaining a grammar point). Why not film yourself, or convert a Slide Show into a movie format.

- search through online materials carefully. There's no point in reinventing the wheel, and if you find good content, use it - and most of the time, it's free anyway.

- Think how to present the materials - where do they go in the online content? How do they lead into what you do in class? How do they support the learner? Can you grade the work done, or track the learner's progress?

- A very important point - will the learner actually be able to use the content? You have to remember that some students are not that technically savvy, and putting up online work they can't access is the same as them doing nothing at all. We have to consider, in some circumstances, that alongside teaching them the subject, we may also need to teach them IT skills.

However you want to do it, from making your own bespoke course to curating materials from a wide variety of sources, I'd encourage you to experiment as much as possible until you find the right blend for you.

Wednesday, 15 May 2013

Four types of language interactor, part two

Following on from the last entry, this one looks at what we can expect and what we can do with our different types, and also what they bring to the table, learning-wise and how (or to what degree) they interact with the language.

The Tourist

From a teaching perspective, the tourist is not the most promising of pupils. They are unlikely to engage with the language to any great depth, nor attain a very high level of fluency. They may use only a few set phrases - indeed, they may actually be happy to achieve only this. This type of learner is likely to be encountered in informal learning situations, e.g. a tourist in the real sense of the word, or, dare I say, an EFL teacher on their first overseas posting, but also in more formal class environments, especially in primary and secondary education, where the focus is on the language as a study subject.

The Tourist generally has little real motivation to learn a language - it has minimal 'value' as a medium of communication.

You might think that the Tourist brings nothing to and takes nothing from the language, but in fact this isn't the case. When you look at the number of loan words in English, for example, you have a demonstration of the Language Tourist in action.

In terms of engaging this kind of learner into a deeper understanding of the language, it's a difficult one. One way forward could be by making them notice the use of common vocabulary between the their L1 and the target L2. It may also be beneficial to point out the advantage being able to 'actively' use another language is. Ultimately, however, it really does boil down to the individual learner and their perceived need of the L2.

The Commuter

The Commuter type of language interactor is perhaps the one type of learner we are most likely to encounter in our classes - typically, they are motivated to learn the language, and will have a relatively low affective filter. They approach language, as it were, from a professional perspective - that is, they go into the language for specific purposes: getting an exam, entry to university, for work purposes etc. While this kind of learner is , from the teacher's perspective, ideal, the issue may be that they are technically very competent, but may not actually be that productive, except within their own range/width of knowledge. It is in this way that they resemble commuters: perfectly able to reach goals within the Language City, but a bit lost when outside their comfort zones.

In some ways, we need to encourage this kind of learner to be a little bit like a tourist - that is, get off the beaten track of their own interests and explore a bit - but also they should be encouraged to believe that they can achieve mastery of the language - that is, they are able to become a citizen or denizen.

The Citizen -

Now, you might think that you won't get many Citizen-type language interactors in your class, and this could well be true if you're overseas in a monolingual group. However, when you're teaching in a so-called Native English Speaking country, you are far more likely to encounter this kind of learner. I deal with Indian, Pakistani, Nepalese, Ghanaian, Kenyan, Tanzanian and Singaporean students, to name a few and they all speak a variety of English already. Well, that should be easy then, shouldn't it?

Wrong. In fact the Citizen can be one of the hardest to teach. After all, they already speak English - what we are doing is teaching a different variety, with different conventions. What we can end up doing, if we are not careful, is make them feel as if their own variety of English is inferior, which of course is a massively demotivating thing. The Citizen has, as it were, their own map of the Language City, and know their own district inside out; When they come into the classroom, we are effectively giving them a new map of a new district, strangely familiar to the one they know, but soon disorienting, and this in turn can lead to disillusionment. For this kind of learner, we need to use their native knowledge of the language to help facilitate learning in others, and also carefully target the kind of language knowledge, whether in systems or skills, that they need, without devaluing their own language variety.

The Denizen

If you have ever taught ESOL/ESL, you will more than likely taught The Denizen - someone who needs to be in the Language City because of personal circumstances, and is required to engage with the language whetehr they like it or not. This group of language interactors can be problematic, as the range of motivation can be enormous. Some Denizens are highly motivated, and in fact are closer to being Citizens; Others are lost, confused and angry, and resent the language entirely. Some Denizens are fluent and efficient communicators; some retreat in acculturation and reach a level of language knowledge that is sufficient (but only just) for them. Denizens, unlike Commuters, may lack learning skills and strategies, or not be able to analyse language in the same way.

However, Denizens are perhaps the great bringers of variety into language. They introduce new expressions and phrases, or retool language into new and interesting forms. Over time, they become citizens in their own right, creating a new district in the Language City, as it were. From the classroom perspective, the more realistic the situations used - that is, real-life issues that the learner is likley to encounter, such as using Council facilities, or applying for a job - the more likely that their motivation will be kept high. Encouraging the confidence to tackle seemingly insurmountable situations is the way to drive this kind of learner towards fluency and, crucially, belief that they 'belong' within the language.

Well, this one way to look at how language users can interact with a language. It has the advantage of being a very flexible, dynamic model, as it should be clear that people's interactions over time can change: tourists can become commuters; commuters, denizens or citizens; denizens can create their own 'district' (=variety) of the language over time, and become citizens in their own right, and citizens can become denizens in another variety of the language, and so on. Give it a try with your own classes - which of your students would you say are Tourists, Commuters, Denizens or Citizens?

The Tourist

From a teaching perspective, the tourist is not the most promising of pupils. They are unlikely to engage with the language to any great depth, nor attain a very high level of fluency. They may use only a few set phrases - indeed, they may actually be happy to achieve only this. This type of learner is likely to be encountered in informal learning situations, e.g. a tourist in the real sense of the word, or, dare I say, an EFL teacher on their first overseas posting, but also in more formal class environments, especially in primary and secondary education, where the focus is on the language as a study subject.

The Tourist generally has little real motivation to learn a language - it has minimal 'value' as a medium of communication.

You might think that the Tourist brings nothing to and takes nothing from the language, but in fact this isn't the case. When you look at the number of loan words in English, for example, you have a demonstration of the Language Tourist in action.

In terms of engaging this kind of learner into a deeper understanding of the language, it's a difficult one. One way forward could be by making them notice the use of common vocabulary between the their L1 and the target L2. It may also be beneficial to point out the advantage being able to 'actively' use another language is. Ultimately, however, it really does boil down to the individual learner and their perceived need of the L2.

The Commuter

The Commuter type of language interactor is perhaps the one type of learner we are most likely to encounter in our classes - typically, they are motivated to learn the language, and will have a relatively low affective filter. They approach language, as it were, from a professional perspective - that is, they go into the language for specific purposes: getting an exam, entry to university, for work purposes etc. While this kind of learner is , from the teacher's perspective, ideal, the issue may be that they are technically very competent, but may not actually be that productive, except within their own range/width of knowledge. It is in this way that they resemble commuters: perfectly able to reach goals within the Language City, but a bit lost when outside their comfort zones.

In some ways, we need to encourage this kind of learner to be a little bit like a tourist - that is, get off the beaten track of their own interests and explore a bit - but also they should be encouraged to believe that they can achieve mastery of the language - that is, they are able to become a citizen or denizen.

The Citizen -

Now, you might think that you won't get many Citizen-type language interactors in your class, and this could well be true if you're overseas in a monolingual group. However, when you're teaching in a so-called Native English Speaking country, you are far more likely to encounter this kind of learner. I deal with Indian, Pakistani, Nepalese, Ghanaian, Kenyan, Tanzanian and Singaporean students, to name a few and they all speak a variety of English already. Well, that should be easy then, shouldn't it?

Wrong. In fact the Citizen can be one of the hardest to teach. After all, they already speak English - what we are doing is teaching a different variety, with different conventions. What we can end up doing, if we are not careful, is make them feel as if their own variety of English is inferior, which of course is a massively demotivating thing. The Citizen has, as it were, their own map of the Language City, and know their own district inside out; When they come into the classroom, we are effectively giving them a new map of a new district, strangely familiar to the one they know, but soon disorienting, and this in turn can lead to disillusionment. For this kind of learner, we need to use their native knowledge of the language to help facilitate learning in others, and also carefully target the kind of language knowledge, whether in systems or skills, that they need, without devaluing their own language variety.

The Denizen

If you have ever taught ESOL/ESL, you will more than likely taught The Denizen - someone who needs to be in the Language City because of personal circumstances, and is required to engage with the language whetehr they like it or not. This group of language interactors can be problematic, as the range of motivation can be enormous. Some Denizens are highly motivated, and in fact are closer to being Citizens; Others are lost, confused and angry, and resent the language entirely. Some Denizens are fluent and efficient communicators; some retreat in acculturation and reach a level of language knowledge that is sufficient (but only just) for them. Denizens, unlike Commuters, may lack learning skills and strategies, or not be able to analyse language in the same way.

However, Denizens are perhaps the great bringers of variety into language. They introduce new expressions and phrases, or retool language into new and interesting forms. Over time, they become citizens in their own right, creating a new district in the Language City, as it were. From the classroom perspective, the more realistic the situations used - that is, real-life issues that the learner is likley to encounter, such as using Council facilities, or applying for a job - the more likely that their motivation will be kept high. Encouraging the confidence to tackle seemingly insurmountable situations is the way to drive this kind of learner towards fluency and, crucially, belief that they 'belong' within the language.

Well, this one way to look at how language users can interact with a language. It has the advantage of being a very flexible, dynamic model, as it should be clear that people's interactions over time can change: tourists can become commuters; commuters, denizens or citizens; denizens can create their own 'district' (=variety) of the language over time, and become citizens in their own right, and citizens can become denizens in another variety of the language, and so on. Give it a try with your own classes - which of your students would you say are Tourists, Commuters, Denizens or Citizens?

Monday, 18 February 2013

Four Types of Language Interactor

Well, half term is upon us, and the work load is shifting round to a vaguely lighter pattern, so I thought it was high time I endeavoured to produce a post. In fact, I'm going back to a previous entry, as I want to expand on how we deal with different types of language user.

Working in FE as I do, I come across a veritable smorgasbord of language learners of different nationalities, backgrounds and ages, and this of course presents very different challenges from those in a monolingual classroom. I have one group that can best be charitably described as :Ladies What Lunch, or more accurately Ladies Who Use The Classroom To Catch Up On The Latest Gossip. While they are all very polite and lovely, they have about as much chance of becoming fluent in English as a fish has of developing opposable thumbs.

There are also students who are, in fact, fluent English users - it's just that they use a different variety of English, such as Hinglish, and much of what they produce either seems very weird to a British English user, or actually prevents them from effectively communicating with others.

I have also taught Academic English, FCE, CAE, so in these groups I tend to get learners with a very determined perspective, knowing precisely the things they want to learn. This is the kind of learner that actually bays for MORE grammar.

Then there is a big fat group of people who need to learn English just to get on - these are a big slice of my ESOL learners, people who for whatever reason have come to live and work in the UK and need English in order to live.

The problem is, what to do with all these different learners when they're all bunged in together in the same class?

A couple of years ago, I gave a presentation at the English UK Teachers' Conference on the subject of Global Englishes, and I came up with the analogy of a language being like a city in the way that people interact with it. A couple of years down the line, I feel my analogy still holds water, so I'd like to (re-)introduce four kinds of Language Interactor, where we usually encounter them, and how to deal with them.

1 The Tourist

The tourist is the kind of learner who is 'just visiting' a language, just as a tourist passes through a place. Tourists look around, take photos, maybe scribble a postcard home - but then leave. Their interaction with the place is relatively minimal, especially if they're the kind of tourist who follows the environmentalist's maxim of 'take nothing but pictures, leave nothing but footprints'. Alternatively, the Tourist wanders round in a kind of terrified daze, petrified of everything they see in this strange new place, clinging on desperately to anything that remids them of home, and deeply glad to get the Hell out when they can.

This kind of learner is really not going to do much with the language. He or she will only work in class, and then not particularly well, and hardly does anything with it when they are outside. In other words, they just come in and out of the language, with little attempt to understand it. Looking back at my career as a neophyte language learner, doing French at school, I can safely say that I was a Language Tourist.

2 The Commuter

The Commuter comes into the city, moving with purpose and speed towards their destination. They work diligently for a given chunk of time, then, at the appointed hour, they move with equal speed and purpose back where they came from. Their movements have a specific goal - namely, do the work necessary and get out of the city again. The Commuter may know everything he or she needs to know between points A and B, but may not have considered that points C,D, or E even exist.

This kind of learner has a very fixed point of view. They may well have exact knowledge of the language, but it is not broad knowledge - for example, they might be able to tell you in excruciating detail all the uses of perfect tenses, but they don't really know enough to use it outside the class or in a natural context. This learner will know enough to pass exams, and function well in English, but for them the language is a means to an end. They are more likely to view language as a subject of study, rather than as a skill.

What Tourists and Commuters have in common is that they are approaching the language from the outside - that is, they don't, as it were, habitually live in the language. This may be literally true: If you have a monolingual group in a Non-English Speaking country, then learners are far more likely to regard language as a study subject rather than a skill - that is, they are travelling into and out of the language. The difference between them is that Tourists tend to have low motivation while Commuters tend to be more highly motivated, although possibly only about specific learning points.

3 The Citizen

The Citizen, is, surprise, surprise, someone who lives in the city. They know the place well, feel at ease in it, and can find their way around with little difficulty. Typically, though, they may take the place for granted: They might live near to a place of historical interest, but never actually visit it at all, simply because it is just there. Likewise, they know their own part of the city intimately well, but there may be quarters and outliers that they are unfamiliar with.

This type of learner is, of course, a Native Language Speaker - but which variety? Just as a city can have different districts with distinctive characters, so can language. In terms of teaching English, this kind of learner can be especially challenging - after all, they speak the language already, so what in fact are we teaching them? It's more akin to instructing someone in the layout of a different part of the city they already inhabit.

4 The Denizen

The term 'Denizen' can mean, simply, 'inhabitant', but it can also mean 'a foreigner who has been granted rights of residence - and sometimes citizenship', and it is in this context that I use the term. The denizen, in our model of a Language City, is someone who has to live within the city, even though it is not necessarily a place entirely familiar to them. Some denizens may know it quite well, and like the place: for others, it is a disquieting, alien, even terrifying place to be. Some are there to work, some there because of family, some for reasons they don't really understand - but the key feature is that they have to live within this city, and they encompass a variety of attitudes towards it, from enthusiastic participants to sullen, angry follwers.

This type of learner is what we might imagine the typical ESOL student to be - someone who has settled in the UK (or another NES country) and who needs to learn English in order to get on, get citizenship etc. We also see that this type of learner's attitude towards and motivation for learning English can vary widely. However, we can also find the Denizen in countries where English, for whatever reason, is a requirement of some kind - it may be, for example, that it is an offical second language, or the medium for judicial/official procedure. We can expect the learner's attitudes in these kind of situations to vary from acceptance to extreme resentment.

The key similarity between the Citizen and the Denizen is that they experience language from within - they are either born into it or have to live within it. However, we can also say that some Citizens are at times like denizens, or even tourists, when they 'visit' other areas of the language. Likewise, some Denizens are on their way to becoming Citizens, or are Citizen-like, as are some Commuters.

This whole model is meant to be dynamic and show that things can and do change within the ways people interact with a language. I hope to show that Kachru's model of language, where you have a kind of 'superior' version of the language in the middle and weaker ones outside of that, is not the only way to look at language learning and acquisition.

In my next post, I'll look at the motivations of each group as language learners (even citizens!), and the problems each pose teachers in the classroom.

Working in FE as I do, I come across a veritable smorgasbord of language learners of different nationalities, backgrounds and ages, and this of course presents very different challenges from those in a monolingual classroom. I have one group that can best be charitably described as :Ladies What Lunch, or more accurately Ladies Who Use The Classroom To Catch Up On The Latest Gossip. While they are all very polite and lovely, they have about as much chance of becoming fluent in English as a fish has of developing opposable thumbs.

There are also students who are, in fact, fluent English users - it's just that they use a different variety of English, such as Hinglish, and much of what they produce either seems very weird to a British English user, or actually prevents them from effectively communicating with others.

I have also taught Academic English, FCE, CAE, so in these groups I tend to get learners with a very determined perspective, knowing precisely the things they want to learn. This is the kind of learner that actually bays for MORE grammar.

Then there is a big fat group of people who need to learn English just to get on - these are a big slice of my ESOL learners, people who for whatever reason have come to live and work in the UK and need English in order to live.

The problem is, what to do with all these different learners when they're all bunged in together in the same class?

A couple of years ago, I gave a presentation at the English UK Teachers' Conference on the subject of Global Englishes, and I came up with the analogy of a language being like a city in the way that people interact with it. A couple of years down the line, I feel my analogy still holds water, so I'd like to (re-)introduce four kinds of Language Interactor, where we usually encounter them, and how to deal with them.

1 The Tourist

The tourist is the kind of learner who is 'just visiting' a language, just as a tourist passes through a place. Tourists look around, take photos, maybe scribble a postcard home - but then leave. Their interaction with the place is relatively minimal, especially if they're the kind of tourist who follows the environmentalist's maxim of 'take nothing but pictures, leave nothing but footprints'. Alternatively, the Tourist wanders round in a kind of terrified daze, petrified of everything they see in this strange new place, clinging on desperately to anything that remids them of home, and deeply glad to get the Hell out when they can.

This kind of learner is really not going to do much with the language. He or she will only work in class, and then not particularly well, and hardly does anything with it when they are outside. In other words, they just come in and out of the language, with little attempt to understand it. Looking back at my career as a neophyte language learner, doing French at school, I can safely say that I was a Language Tourist.

2 The Commuter

The Commuter comes into the city, moving with purpose and speed towards their destination. They work diligently for a given chunk of time, then, at the appointed hour, they move with equal speed and purpose back where they came from. Their movements have a specific goal - namely, do the work necessary and get out of the city again. The Commuter may know everything he or she needs to know between points A and B, but may not have considered that points C,D, or E even exist.

This kind of learner has a very fixed point of view. They may well have exact knowledge of the language, but it is not broad knowledge - for example, they might be able to tell you in excruciating detail all the uses of perfect tenses, but they don't really know enough to use it outside the class or in a natural context. This learner will know enough to pass exams, and function well in English, but for them the language is a means to an end. They are more likely to view language as a subject of study, rather than as a skill.

What Tourists and Commuters have in common is that they are approaching the language from the outside - that is, they don't, as it were, habitually live in the language. This may be literally true: If you have a monolingual group in a Non-English Speaking country, then learners are far more likely to regard language as a study subject rather than a skill - that is, they are travelling into and out of the language. The difference between them is that Tourists tend to have low motivation while Commuters tend to be more highly motivated, although possibly only about specific learning points.

3 The Citizen

The Citizen, is, surprise, surprise, someone who lives in the city. They know the place well, feel at ease in it, and can find their way around with little difficulty. Typically, though, they may take the place for granted: They might live near to a place of historical interest, but never actually visit it at all, simply because it is just there. Likewise, they know their own part of the city intimately well, but there may be quarters and outliers that they are unfamiliar with.

This type of learner is, of course, a Native Language Speaker - but which variety? Just as a city can have different districts with distinctive characters, so can language. In terms of teaching English, this kind of learner can be especially challenging - after all, they speak the language already, so what in fact are we teaching them? It's more akin to instructing someone in the layout of a different part of the city they already inhabit.

4 The Denizen

The term 'Denizen' can mean, simply, 'inhabitant', but it can also mean 'a foreigner who has been granted rights of residence - and sometimes citizenship', and it is in this context that I use the term. The denizen, in our model of a Language City, is someone who has to live within the city, even though it is not necessarily a place entirely familiar to them. Some denizens may know it quite well, and like the place: for others, it is a disquieting, alien, even terrifying place to be. Some are there to work, some there because of family, some for reasons they don't really understand - but the key feature is that they have to live within this city, and they encompass a variety of attitudes towards it, from enthusiastic participants to sullen, angry follwers.

This type of learner is what we might imagine the typical ESOL student to be - someone who has settled in the UK (or another NES country) and who needs to learn English in order to get on, get citizenship etc. We also see that this type of learner's attitude towards and motivation for learning English can vary widely. However, we can also find the Denizen in countries where English, for whatever reason, is a requirement of some kind - it may be, for example, that it is an offical second language, or the medium for judicial/official procedure. We can expect the learner's attitudes in these kind of situations to vary from acceptance to extreme resentment.

The key similarity between the Citizen and the Denizen is that they experience language from within - they are either born into it or have to live within it. However, we can also say that some Citizens are at times like denizens, or even tourists, when they 'visit' other areas of the language. Likewise, some Denizens are on their way to becoming Citizens, or are Citizen-like, as are some Commuters.

This whole model is meant to be dynamic and show that things can and do change within the ways people interact with a language. I hope to show that Kachru's model of language, where you have a kind of 'superior' version of the language in the middle and weaker ones outside of that, is not the only way to look at language learning and acquisition.

In my next post, I'll look at the motivations of each group as language learners (even citizens!), and the problems each pose teachers in the classroom.

Monday, 14 January 2013

Classroom activity - Would I Lie To You?

Just a quick entry about a classroom activity I trialled today and worked well - I've called it 'would I lie to you?'after the BBC TV programme.

This activity works best at intermediate level and above, although I used it with an E3 group, who are actually a good pre-intermediate level, and can be used as a way of writing present perfect sentences and asking questions in past simple to elicit further information.

Procedure:

Teacher writes something on the board about themselves, e.g. 'I have written a novel'. Tell the students that they must ask a question to get more information. Put students in pairs/groups, and get them to brainstorm questions. They must then decide which question would be the best to ask, and , of course, ask it. The aim is to produce questions using past dime, but monitor and allow questions in other tenses if appropriate, e.g. 'How much money have you made?', as one of my students came up with :)

Place the students into groups of four, and tell them that they must now write down something about themselves that no-one else in the room knows. Make sure they use ' I have....' Or 'I have never....' Model some sentences if necessary, e.g. 'I have met The Queen' or 'I have never learned to ride a bike'. Students write down their secret on a piece of paper, and share it with their group. The teacher then collects the secrets, and distributes them to another group.

The groups must then decide a question for each secret to ask to get more information. Teacher monitors to help/ suggest etc. The groups then ask each member of the other group the same question, and decide which person is telling the truth. If they guess correctly, they get a point. It is then the other group's turn.

This was a fun activity, and very good for consolidating tense use, although some students found it difficult at first to make up a story - however, by the end, they became extremely inventive!

This activity works best at intermediate level and above, although I used it with an E3 group, who are actually a good pre-intermediate level, and can be used as a way of writing present perfect sentences and asking questions in past simple to elicit further information.

Procedure:

Teacher writes something on the board about themselves, e.g. 'I have written a novel'. Tell the students that they must ask a question to get more information. Put students in pairs/groups, and get them to brainstorm questions. They must then decide which question would be the best to ask, and , of course, ask it. The aim is to produce questions using past dime, but monitor and allow questions in other tenses if appropriate, e.g. 'How much money have you made?', as one of my students came up with :)

Place the students into groups of four, and tell them that they must now write down something about themselves that no-one else in the room knows. Make sure they use ' I have....' Or 'I have never....' Model some sentences if necessary, e.g. 'I have met The Queen' or 'I have never learned to ride a bike'. Students write down their secret on a piece of paper, and share it with their group. The teacher then collects the secrets, and distributes them to another group.

The groups must then decide a question for each secret to ask to get more information. Teacher monitors to help/ suggest etc. The groups then ask each member of the other group the same question, and decide which person is telling the truth. If they guess correctly, they get a point. It is then the other group's turn.

This was a fun activity, and very good for consolidating tense use, although some students found it difficult at first to make up a story - however, by the end, they became extremely inventive!

Monday, 7 January 2013

Web Profiles

Well, it's back to the grind once more. I arrived back at work on the third for a day of speeches and workshops and Working Stuff Out On Flipchart Paper. Reading College is actually not bad at delivering lots of CPD - there's quite a variety, although it does tend to be aimed at newer teachers, I find. In fact, I have delivered CPD sessions myself, something I quite enjoy. It's always nice to do the teacher equivakent of a Show and Tell, and have your work recognised.

Doing one of the training sessions last week, however, I was a little surprised to see a worksheet with something a bit familiar on it. A web of some kind.

'Right, we've got these here', said the CPD leader in our room, 'Now, what I think you've got to do with these is draw a little spider on them, showing where you think your department are in relation to one of these key criteria....'

I looked at the diagram. There was no doubt about it - it was MY idea. The trouble was, it was a poor imitation of it, and the person leading the exercise didn't understand it!

What a bloody cheek.

Now, I wouldn't mind if they'd acknowledged my name somewhere - I feel ideas should be shared, within reason. I also wouldn't have minded so much if they'd deployed it correctly, which they didn't. It was the combination of using the idea poorly and no acknowledgement which really narked me.

So, I hear you cry, what is this idea then?

Simple: It's a Web Profile, or a GLAW (Global Language/Learning Ability Web) Profile, and I'm going to share with you how it works.

The idea came out of a problem I'd been toying with during tutorial sessions with my students - how do you show a learner's ability and progress in the different areas of skills and systems (Reading, Writing, Listening, Speaking, Vocabulary and Grammar) in relation to each other?

I began by toying with circles and blocks - the idea being that the bigger the circle or block, the greater the learner's knowledge of the skill or system represented. Then I reasoned that learning a language is all about expanding knowledge - that is, it is a holistic experience: In order to represent this, you need something that expands from a middle point.

After toying with circles and different gradients of colour, I then thought about segments to represent the different skills and systems we expect a learner to become proficient in, and suddenly, this was born:

In short, a simple web. Here's how it works. Let's label it with our skills and systems:

In this example, I've put the receptive skills on the left, the productive on the right and vocabulary and grammar at the bottom. I should point out that this is the simple version: We could quite easily break down vocabulary, for example, into passive and active knowledge (or at least that's what a couple of my students did when presented with this - but more on that later).

We then add the levels of knowledge. In the diagram below, I've used the CEFR scales from A1 to B2 as an example, with A1 representing the centre of the web and so on outwards:

Of course, we could use ESOL levels from E1 to L2, or add extra external layers to the web. We could also use criteria like the IELTS score scales or TOEFL boundaries. The whole point is that the web, as it expands, indicates greater profiency in the learner's language knowledge and mastery.

So, how do we use it? Simplicity itself: You just colour in the segments. So, you might have a learner who you judge to be at B1 as a speaker, but hasn't reached that level in writing. You just shade in the appropriate level. What immediately becomes apparent is the relationship between the different skills and systems - for example, someone who is poor in reading is likely to also have poor vocabulary, while someone else may have excellent grammar knowledge but finds it difficult to be productive.

We can also use two or more colours, to represent whether a learner's use of a particular area is weak, emergent or consolidated. In the (slightly exaggerated) example below, I've used a two-colour system (basically two flourescent markers ):

The beauty of this system is that it visually represents the learner's global, holistic use of a language. I have given these to students to complete themselves, then got them to compare their ideas with my own. During tutorials, it really allows the learner to understand which areas they need to focus on, and the relationships between the different areas that make up language.

However, it doesn't stop there: this profiling system can easily be adapted to other learning areas as well - indeed, several teachers in my college are looking how it can be used to help their students in areas such as Maths, Digital Photography and Plumbing!

We can also make it even more complex - for example, I did play around with adding all the key 'Can Do' statements for CEFR on it seeking to highlight specific targets, but keeping it simple seems to work better.

And THAT is how this is meant to work!

Feel free to experiment with it and use it - all I ask is a little acknowledgement :)

Doing one of the training sessions last week, however, I was a little surprised to see a worksheet with something a bit familiar on it. A web of some kind.

'Right, we've got these here', said the CPD leader in our room, 'Now, what I think you've got to do with these is draw a little spider on them, showing where you think your department are in relation to one of these key criteria....'

I looked at the diagram. There was no doubt about it - it was MY idea. The trouble was, it was a poor imitation of it, and the person leading the exercise didn't understand it!

What a bloody cheek.

Now, I wouldn't mind if they'd acknowledged my name somewhere - I feel ideas should be shared, within reason. I also wouldn't have minded so much if they'd deployed it correctly, which they didn't. It was the combination of using the idea poorly and no acknowledgement which really narked me.

So, I hear you cry, what is this idea then?

Simple: It's a Web Profile, or a GLAW (Global Language/Learning Ability Web) Profile, and I'm going to share with you how it works.

The idea came out of a problem I'd been toying with during tutorial sessions with my students - how do you show a learner's ability and progress in the different areas of skills and systems (Reading, Writing, Listening, Speaking, Vocabulary and Grammar) in relation to each other?

I began by toying with circles and blocks - the idea being that the bigger the circle or block, the greater the learner's knowledge of the skill or system represented. Then I reasoned that learning a language is all about expanding knowledge - that is, it is a holistic experience: In order to represent this, you need something that expands from a middle point.

After toying with circles and different gradients of colour, I then thought about segments to represent the different skills and systems we expect a learner to become proficient in, and suddenly, this was born:

In short, a simple web. Here's how it works. Let's label it with our skills and systems:

In this example, I've put the receptive skills on the left, the productive on the right and vocabulary and grammar at the bottom. I should point out that this is the simple version: We could quite easily break down vocabulary, for example, into passive and active knowledge (or at least that's what a couple of my students did when presented with this - but more on that later).

We then add the levels of knowledge. In the diagram below, I've used the CEFR scales from A1 to B2 as an example, with A1 representing the centre of the web and so on outwards:

Of course, we could use ESOL levels from E1 to L2, or add extra external layers to the web. We could also use criteria like the IELTS score scales or TOEFL boundaries. The whole point is that the web, as it expands, indicates greater profiency in the learner's language knowledge and mastery.

So, how do we use it? Simplicity itself: You just colour in the segments. So, you might have a learner who you judge to be at B1 as a speaker, but hasn't reached that level in writing. You just shade in the appropriate level. What immediately becomes apparent is the relationship between the different skills and systems - for example, someone who is poor in reading is likely to also have poor vocabulary, while someone else may have excellent grammar knowledge but finds it difficult to be productive.

We can also use two or more colours, to represent whether a learner's use of a particular area is weak, emergent or consolidated. In the (slightly exaggerated) example below, I've used a two-colour system (basically two flourescent markers ):

The beauty of this system is that it visually represents the learner's global, holistic use of a language. I have given these to students to complete themselves, then got them to compare their ideas with my own. During tutorials, it really allows the learner to understand which areas they need to focus on, and the relationships between the different areas that make up language.

However, it doesn't stop there: this profiling system can easily be adapted to other learning areas as well - indeed, several teachers in my college are looking how it can be used to help their students in areas such as Maths, Digital Photography and Plumbing!

We can also make it even more complex - for example, I did play around with adding all the key 'Can Do' statements for CEFR on it seeking to highlight specific targets, but keeping it simple seems to work better.

And THAT is how this is meant to work!

Feel free to experiment with it and use it - all I ask is a little acknowledgement :)

Tuesday, 1 January 2013

Resolutions?

First of all, Happy New Year everyone, and I hope that you all have great time in the classroom over 2013.

Now, I'm not one for making resolutions generally at this time of year, as I find that if I do, I end up a) with a ridiculously long list of propositions, b) I start off trying to do them at a manically high level of activity that is unsustainable and c) I rapidly get bored of them by about 3.30pm on the 1st.

One problem with making resolutions is that they are often made within the framework of giving up or forgoing something, e.g. 'I'm going to give up smoking'. The fact that they are worded in this way means that we end up in our heads fighting our way away from something, rather than making the resolution about an aim towards something. Taking the example above, if we make it 'I'm going to be healthier next month by saving money, as I won't be smoking this month' makes it seem something more concrete and attainable.

Anyway, what has this to do with an ELT Journal? Well, two things - firstly, a short list of resolutions for myself, aiming to be as positive as possible:

1) I'm going to keep this journal more regularly, with a greater focus on classwork.

2) By the middle of June, I will have handed out fewer photocopied pages to students.

3) I will make greater use of the students' various tech gadgets - smartphones, tablets, laptops, etc - to creater more differentiated approaches.

That, I think, will do.

Secondly, just a thought about using New Year Resolutions in class. The obvious one is as practice and consolidation of future forms - as you probably noticed above, I've used will, going to and future perfect in my little list. It depends, of course, on the level of your students, but resolutions can be a great way for learners to differentiate between future predictions (using will) and future plans and intentions (using going to). One thing I did last year was make students write down resolutions and predictions for the next 6 months for themselves, a classmate, me, and the world on a piece of paper. We then folded them up and put them in a box, which I sealed and didn't open until the last lesson of the year.

Another technique is to get students to make suggestions for what another person in class should do in the year to come - this is a change of focus towards giving advice of course, but it can be useful for getiting students to produce will/'ll/going to statements as well - learners discuss what other students have said, and reply to the suggestions made for themselves.